Species: Cattle, sheep, horses, camelids, deer, dogs, cats, birds

Specimen: 2-4g faeces per animal

Container: Plastic pottle

Collection protocol: Collect samples directly from rectum of animal (not from the ground unless freshly passed onto clean yard)

Special handling/shipping requirements:

Submit fresh or store in a refrigerator* until transport to a laboratory. Do not freeze.

*It is important that faecal samples for larval cultures are not refrigerated at all. In cases where both FECs and larval cultures are required on the same set of samples it is recommended that a sub-sample be removed from each individual sample and pooled. The individual samples for FEC can be refrigerated while the pooled sample should be clearly identified as being for larval culture and kept at room temperature.

General information about the disease:

Grazing ruminants in New Zealand are rarely free of worm infection, though effects on stock health and productivity vary widely. Clinical effects of enteric parasitism include ill thrift, diarrhoea, anaemia, and death in severe cases. The degree of damage is influenced by the numbers and identities of the parasites present, host age, immunity, general health, and nutrition.

General information about when the test is indicated:

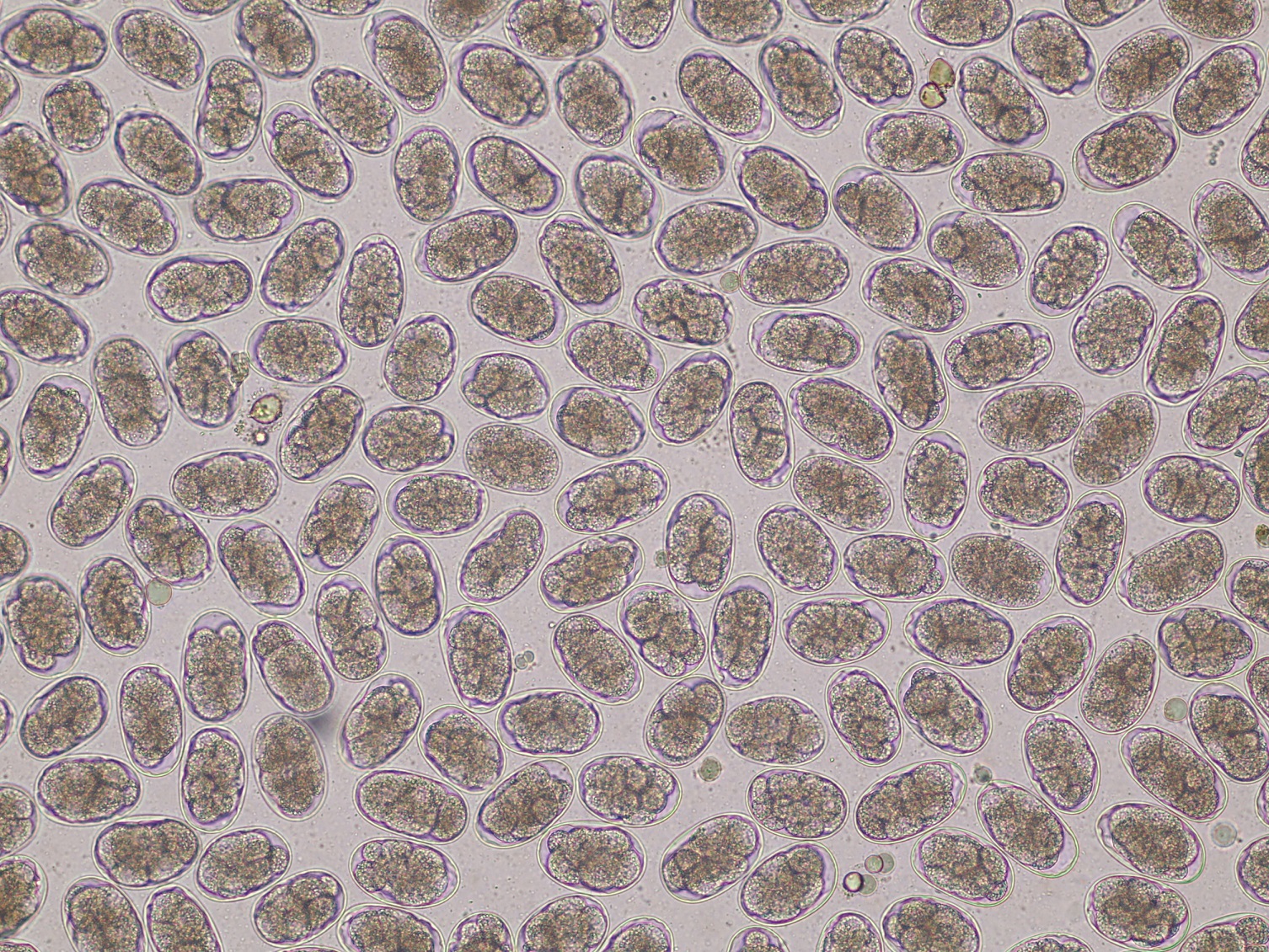

FECs are used to monitor the effectiveness of worm control programmes, help in the differential diagnosis of cases of scouring and ill thrift, aid drench decision-making, and investigate suspected drench resistance.

Any statement regarding significance of FECs will only be a guide. Interpretation must take into account the age, class, origin, state of nutrition, environment, stage of season, and concurrent disease state of infected animals.

SHEEP

FECs provide a relatively robust estimate of worm burdens in sheep and goats, especially those in the first year of life. An exception applies in the case of Nematodirus infections, where limited reliance should be placed on egg counts for diagnostic purposes. A FEC of 500 eggs per gram is generally considered high enough to require treatment in order to limit pasture contamination and subclinical disease. Treatment may be advisable at lower counts depending on the circumstances.

CATTLE

FEC in cattle are considered more variable and of less diagnostic value than those in small ruminants due to the stereotypic suppression of Ostertagia ovulation as host immunity develops. However, Ostertagia infections rarely occur in isolation and Cooperia and Trichostrongylus egg production may not be affected by host immunity to the same degree. Consequently, in mixed infections, FECs may still provide useful guidelines regarding herd parasite status, especially in cattle less than 18 months old. FECs in older cattle are frequently unreliable unless a breakdown in host immunity reveals high FECs. In cattle, a FEC of 150-250 is generally considered high enough to require treatment. Clinically affected cattle with diarrhoea often have >1,000 epg.

HORSES

FECs are only an approximate guide to worm burden. Clinical history and knowledge of seasonal pattern of parasites in specific geographical regions will assist in interpretation of FECs. The following FECs may indicate clinical disease:

- Up to 15 months of age – 100 epg

- 2-year-old – 200 epg

- 2-6-year-old – 400 epg

- >6-year-old – 600 epg

Comparison with other related tests:

FECs provide little information on the identity of the worm genera represented. This can be overcome by the use of faecal larval cultures in conjunction with FEC. FEC and larval culture are both necessary for the calculation of faecal egg count reductions to determine drench resistance. Total worm counts on abomasal and small intestinal contents can provide more accurate information on parasite burden than FECs.

Serum pepsinogen may be used as an estimate of abomasal ostertagiasis in young cattle.

FEC is part of the small animal diarrhoea panel (FEC, coccidia, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Giardia, and Crytposporidium).