KATHRYN JENKINS

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) can quickly and easily identify whether an enlarged lymph node is hyperplastic/reactive, inflamed, or neoplastic (e.g. lymphoma). It can also aid in the identification of potential metastatic disease (e.g. mast cell tumours, carcinoma, histiocytic sarcoma), and can also identify uncommon infectious agents.

A recent case highlighted the usefulness of lymph node FNA when identifying the cause of a skin nodule in a young cat.

Clinical history:

A one-year-old female spayed domestic shorthair cat was presented for a 6mm mass on her lower lip, and significant right submandibular lymph node swelling. The mass had appeared quickly, but there had been no change in size over the previous 10 days. FNA was performed on the lymph node, and the mass was biopsied and sent for histopathology.

Laboratory findings:

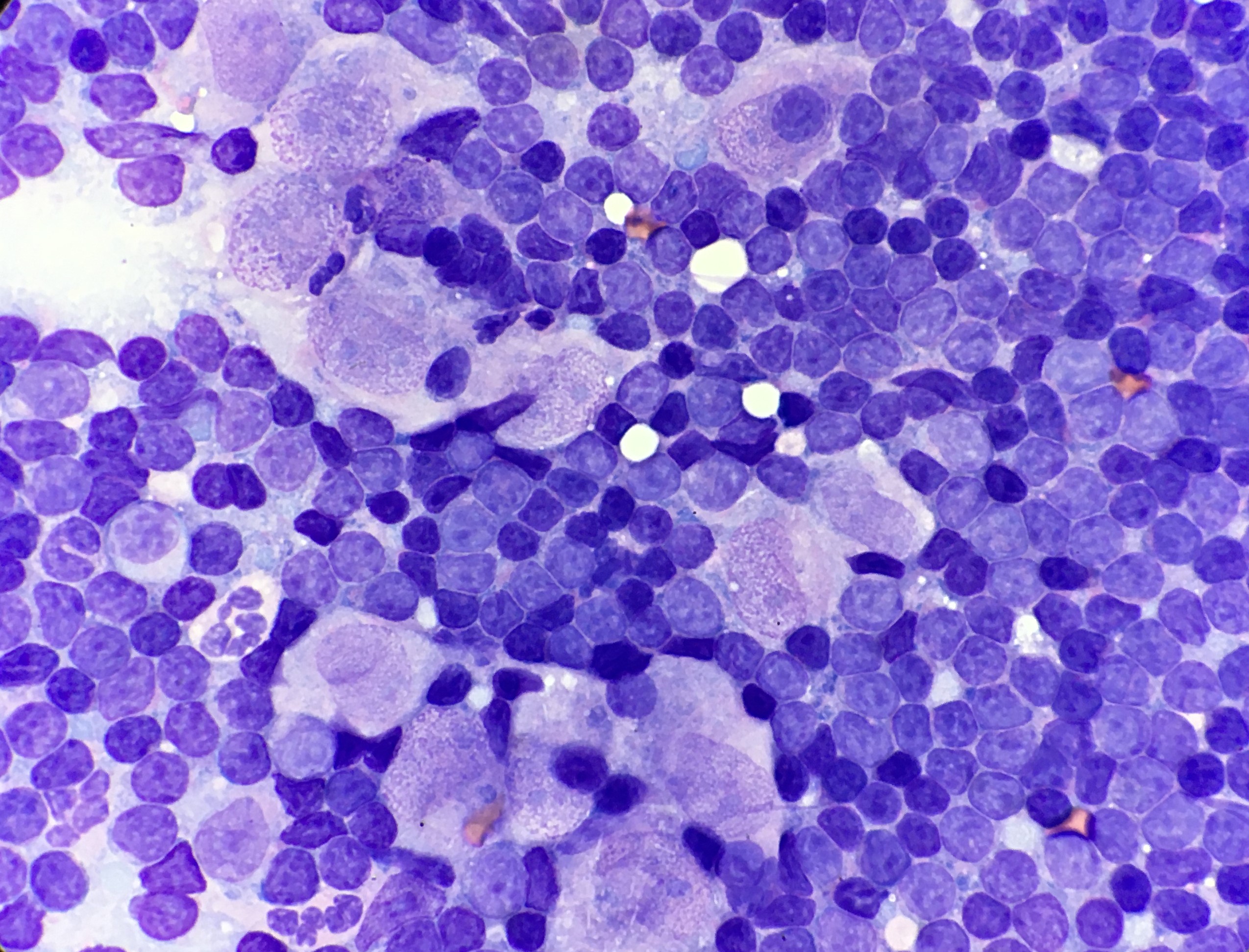

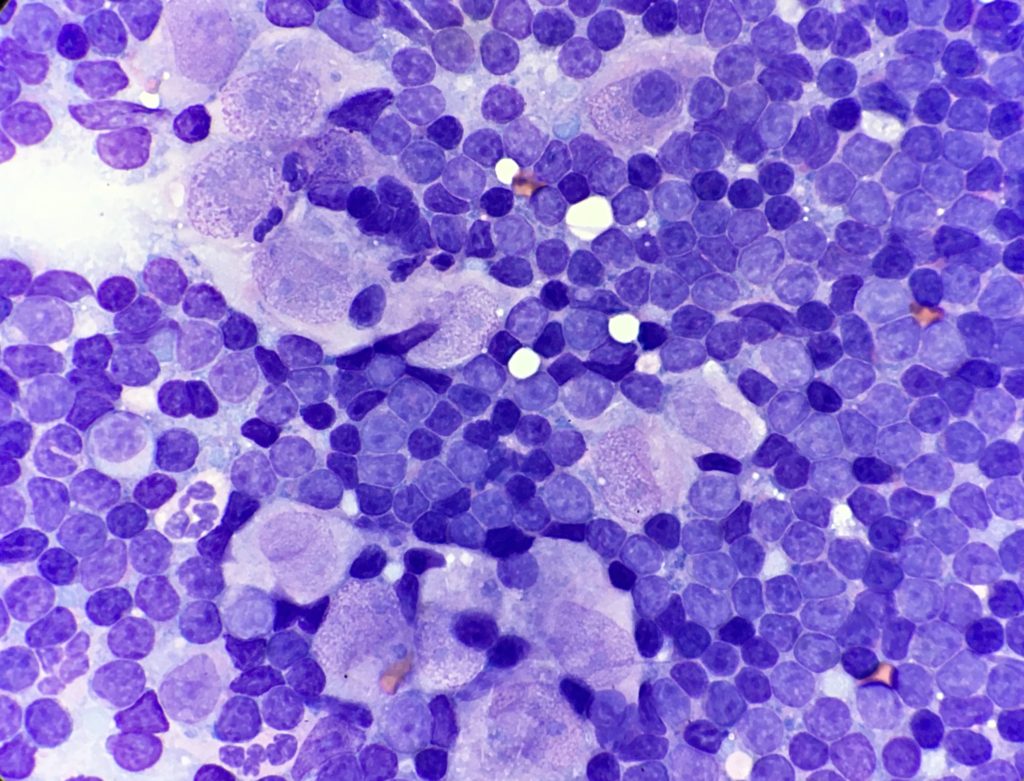

Cytology of the lymph node contained a well-preserved population of mixed lymphocytes, with scattered large epithelioid macrophages, and low numbers of neutrophils, amidst scant amounts of blood on a basophilic proteinaceous background (Figures 1 and 2).

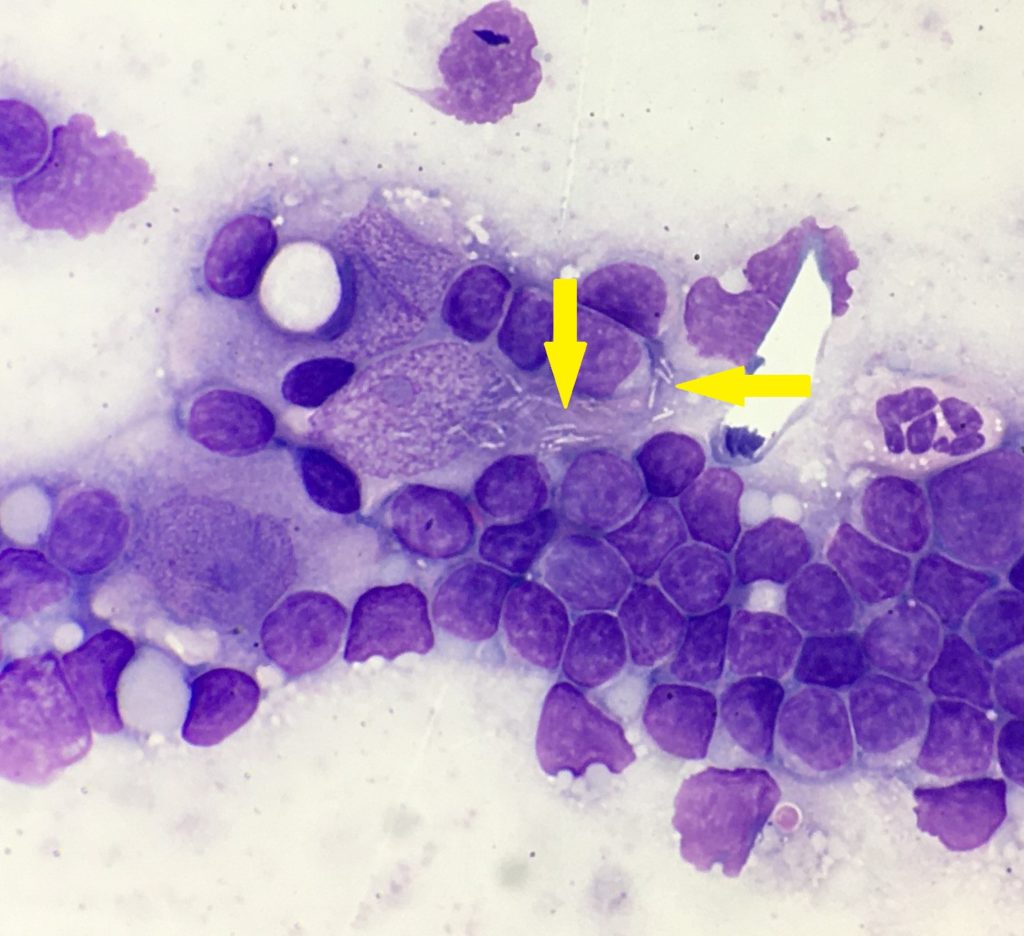

The lymphoid population were mostly small mature lymphocytes, with fewer intermediate lymphocytes and rare large lymphocytes, with occasional plasma cells and reactive appearing lymphocytes. Epithelioid macrophages had moderate amounts of pale basophilic cytoplasm, oval to slightly irregular nuclei, with stippled chromatin and 1-2 small nucleoli. The cytoplasm contained small numbers of negatively staining thin refractile rod-shaped structures, consistent with Mycobacteria. One of the cytology smears was submitted for additional acid-fast stains, which was positive, providing further confirmation of Mycobacterial infection.

Histopathology of the lip mass comprised a dense nodular multifocal to coalescing infiltrate of macrophages and neutrophils, with multifocal areas of necrosis and haemorrhage. This pyogranulomatous inflammation was supportive of a diagnosis of Mycobacteria, however these organisms are not readily observed on routine H&E sections. Subsequent acid-fast stains were positive for small numbers of Mycobacterial organisms, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous Mycobacteriosis, with dissemination to the draining lymph node.

Discussion:

Classical feline leprosy syndrome, can be caused by several slow growing and fastidious species (including Mycobacterium lepraemurium, M. visibile, M. tarwinense, and M. leparefelis). The syndrome is progressive, starting with cutaneous nodules, with possible spread to regional lymph nodes later in the course of disease, followed by dissemination to internal organs (such as liver or spleen). Occasionally they can demonstrate a more aggressive clinical course. Excision of solitary lesions can prove curative, however adjunctive antimicrobial therapy (using two or three drugs effective against slowly growing mycobacteria) is recommended, especially once disease progression has been identified.

The organisms involved with classical feline leprosy syndrome are not thought to pose a zoonotic risk. However, this contrasts with tuberculous forms of Mycobacteria (such as M. bovis), which do have zoonotic potential. M. bovis has previously been isolated from domestic cats throughout New Zealand, and historically these cases arose from areas where M. bovis was also present in the wildlife population (especially the brush-tailed possum). Lesion distribution in these cats included the skin, submandibular and mesenteric lymph nodes, as well as generalised infection. Recent cases in the United Kingdom have also been linked to the feeding of raw pet food diets.

Given Mycobacteria species cannot be differentiated by cytology or histopathology alone, confirmation of Mycobacteria species is recommended. Mycobacteria are often non-culturable, and speciation of Mycobacteria can be achieved by PCR on fresh tissue, which is the preferred sample type. Tissue from cytology slides and formalin fixed tissue may also be utilised, in cases where fresh tissue is not available.

PCR was performed on both fixed and fresh tissue submitted for the case, with the PCR product from fresh tissue being 100% identical to M. lepraemurium. This is the most common cause of classical feline leprosy syndrome, with lesions commonly found on the head area in young cats. Low bacterial numbers in both cytology and histopathology are not uncommon, although high bacterial numbers can also occur. These lesions often ulcerate later in the course of disease, with dissemination uncommonly reported.

Thank you to Brendon Bullen from Kelburn Vets for submitting this interesting case.

References:

O’Brien, C. et al. Feline leprosy due to Mycobacterium lepraemurium. Journal Feline Medicine and Surgery, Vol. 19 2017.

O’Halloran, C et al. Tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in pet cats associated with feeding a commercial raw food diet. Journal Feline Medicine and Surgery, Vol. 21(8) 2019.

De Lise, G.W. et al. A report of tuberculosis in cats in New Zealand, and the examination of strains of Mycobacterium bovis by DNA restriction endonuclease analysis. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 39, 1990.