BERNIE VAATSTRA

This month we present two cases caused by the same aetiological agent.

Case 1:

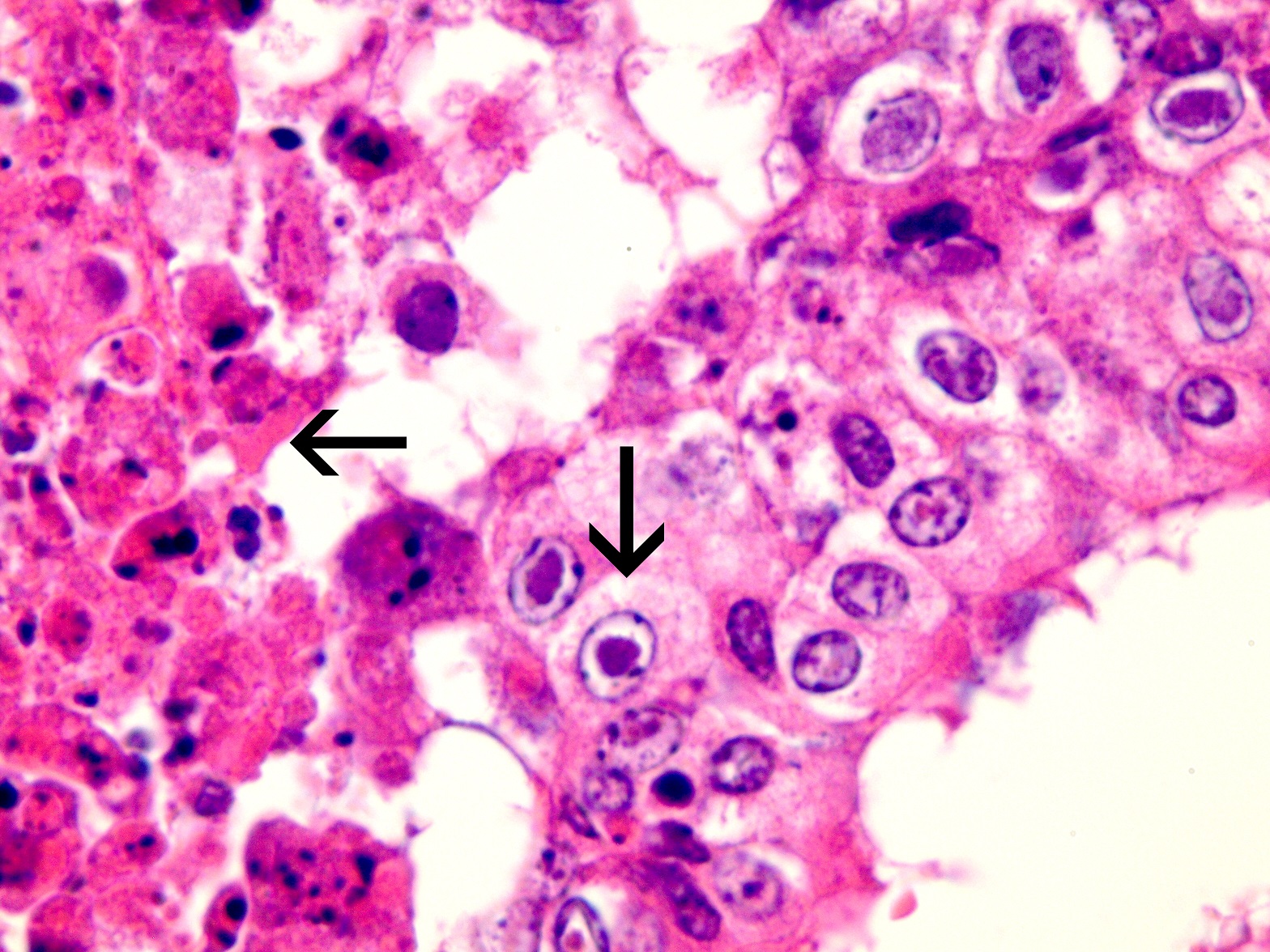

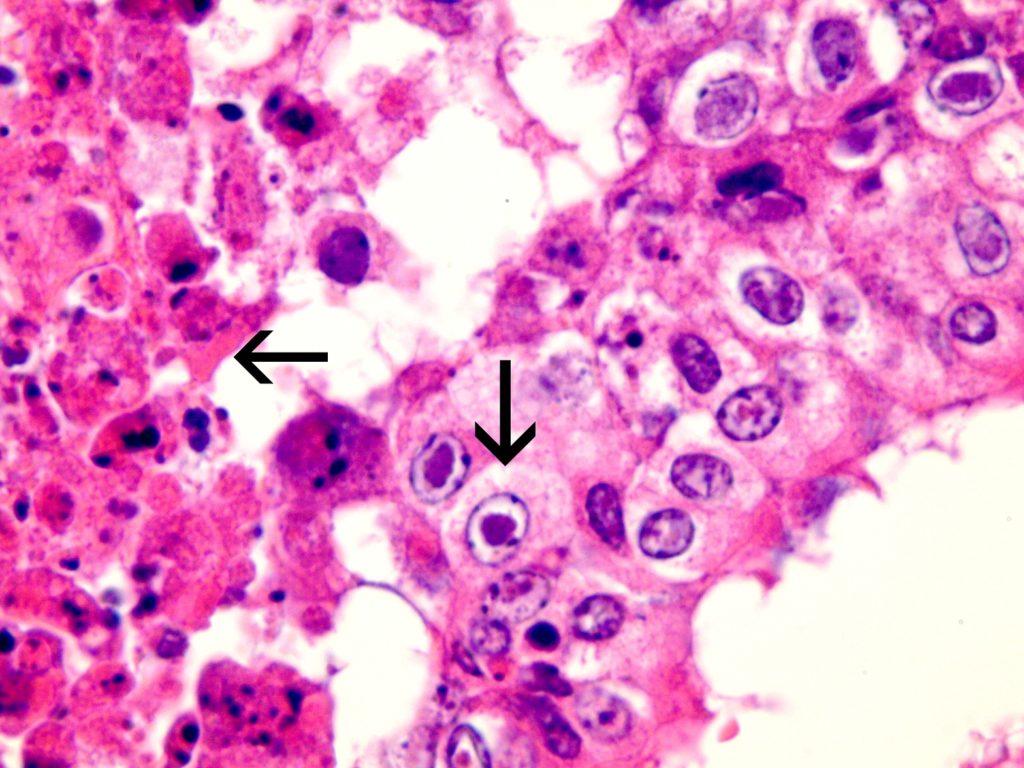

Seven first-calving Friesian heifers from a Waikato dairy herd developed fever and respiratory distress and three died after returning from grazing and presumably being exposed to BHV-1 circulating in the home herd. Necropsy findings included severe necrotising tracheitis (Figure 1) and pneumonia. Histological examination of trachea and lung revealed tell-tale lesions and secondary bacterial pneumonia (Figure 2).

Case 2:

An outbreak of respiratory disease occurred in mixed-age dairy cows on a farm in Taranaki. Five to ten cows developed fevers of >40°C, noisy respiration, nasal discharge (Figure 3), and decreased milk production. Two cows were sampled for biochemistry and serology testing. Both had elevated GGT activities suggesting biliary damage due to sporidesmin toxicity.

Diagnosis: Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR).

Discussion:

Bovine Herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) is a common cause of respiratory and genital infection in New Zealand cattle. There are three subtypes recognised worldwide: BHV-1.1, BHV-1.2a and BHV-1.2b. Only subtype 1.2b is reported in New Zealand (Wang et al 2006). This subtype is associated with respiratory disease (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis – IBR) and genital disease (bovine pustular vulvovaginitis and balanoposthitis), but not abortion or encephalitis. The virus is highly infectious and seroprevalence is high across New Zealand farms (>65%), increasing with cow age.

Acute IBR is characterised by one or more of nasal discharge, rhinitis, tracheitis, conjunctivitis, milk drop, and fever. Some cattle present with conjunctivitis only. In general, symptoms are short lived and self-limiting but can be prolonged and severe where there is secondary bacterial infection or underlying/concurrent disease. It is worth noting that many infections will be subclinical and therefore, when clinical outbreaks occur, underlying factors such as BVD infection, parasitism, nutritional stress, or mixing of naïve cattle with an infected population should be considered.

In recent seasons, we have received submissions from a number of significant IBR outbreaks. Along with the samples, we often field questions about the most appropriate sample types and tests to use.

Gribbles Veterinary offers two ante-mortem diagnostic tests for IBR – antibody ELISA and PCR.

Which test should you use to confirm IBR during an outbreak of bovine respiratory disease?

We advise PCR as the first line test in this situation as it detects viral shedding by acutely infected cattle. Collection of nasal or conjunctival dry swabs from 2-3 cows increases the probability of detection given variable shedding rates. At the same time, collect serum samples to hold in case the PCR result is ‘not detected’.

How long after the onset of clinical signs, will the PCR detect virus?

Viral shedding may continue for approximately 14 days based on testing of experimentally infected naïve cattle (Nandi et al, 2009).

What if the PCR returns a ‘not detected’ result in cattle suspected of having IBR?

In this situation, antibody ELISA testing may provide additional information but needs to be interpreted with caution. Cattle develop a detectable antibody response from approximately 2-3 weeks post BHV-1 infection. Therefore, in an outbreak situation, seroconversion demonstrated by an initial negative IBR antibody ELISA followed by a positive antibody ELISA also confirms infection. Note that a single positive IBR ELISA does not confirm clinical infection given the high natural seroprevalence to IBR.

If both IBR PCR and antibody ELISA are negative in an animal with a recent history of respiratory disease, IBR is unlikely.

Is it possible for cattle to have a positive IBR antibody ELISA and PCR concurrently?

This occurs rarely in the subacute stages of infection when an antibody response has developed but there is still residual virus detectable, or in cattle with a latent IBR infection that recrudesces due to concurrent illness or stress (see case 2).

Is it possible to distinguish cattle with natural immunity to IBR from those vaccinated with a marker vaccine?

A specific IBR-gE ELISA will differentiate between natural immunity and vaccinal immunity in cattle vaccinated with the marker vaccine. However, commercial laboratories in NZ currently offer only the IBR-gB ELISA, which detects antibodies produced to both natural infection and vaccination.

Does the IBR PCR distinguish between different BHV-1 subtypes?

No. If one of the exotic subtypes (BHV1.1, BHV1.2a) is suspected based on clinical presentation (e.g. abortions, encephalitis, abnormally severe respiratory disease outbreak with no evidence of bacterial involvement), notification of MPI is required for further investigation.

Case studies:

In case 1, BHV-1 and Mannheimia haemolytica were detected by PCR on fresh lung tissue. The lesions seen on histological examination of the trachea and lung were compatible with IBR and secondary bacterial pneumonia (including characteristic herpesviral inclusions indicated in Figure 2).

The serology of both cows sampled in case 2 were positive for IBR antibody ELISA and positive IBR PCR on nasal swabs. The stress of facial eczema in cows previously exposed and immune to IBR may have resulted in recrudescence of infection, viral shedding, and transmission to naïve cows within the herd.

Many thanks to Peter Benn of Energy Vets Taranaki Ltd. and Axel de Zeeuw of Vetora Putaruru, for the case submissions and photographs.

References:

Wang J, Horner GW, O’Keefe JS. Genetic characterisation of bovine herpesvirus 1 in New Zealand. NZ Vet J. 54:61-6, 2006

Nandi S, Kumar M, Manohar M, Chauhan RS. Bovine herpes virus infections in cattle. Anim Health Res Rev. 10:85-98, 2009.