GEOFF ORBELL

We are starting to see cases of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli (AEEC) in weaned calves this season. This is likely underdiagnosed in New Zealand as no ante-mortem tests are available, and post-mortem examinations often yield false-negative diagnoses due to intestinal autolysis, or lack of submission of a full range of gastrointestinal samples for histology.

Clinical history:

Forty weaned dairy calves out of 100 animals across three different mobs (one autumn-born and two spring-born) presented with ill thrift, weight loss, and scouring. Three calves had died over the last week so the local veterinarian decided to perform a sacrificial post mortem on a moribund calf.

A full range of fresh and fixed tissues including spiral colon were submitted to the laboratory.

Histopathology findings:

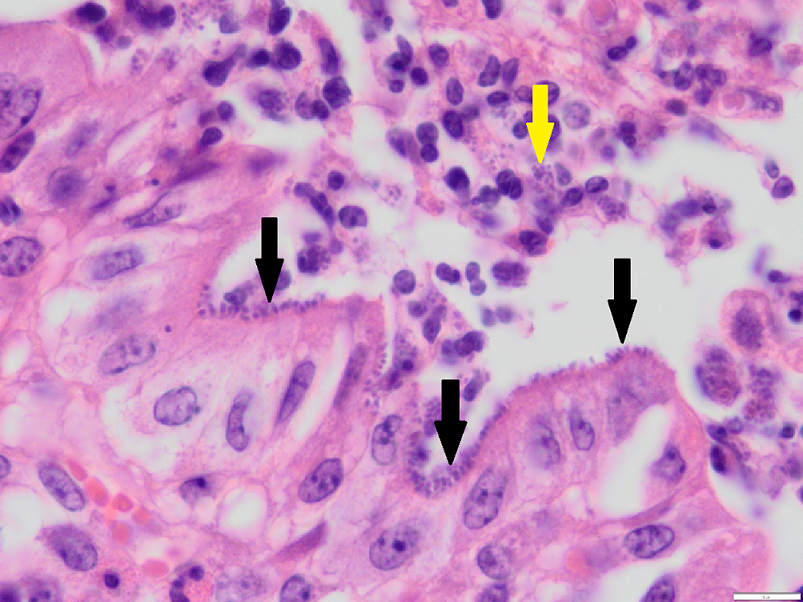

Histology on fixed tissues revealed changes in the gastrointestinal tract consistent with parasitism. In the large intestine there was also erosion and attenuation of the mucosa, with low numbers of degenerate neutrophils. In the adjacent intact mucosa, numerous short bacilli were identified palisading along the brush border consistent with AEEC (enteropathogenic E. coli).

Discussion:

Attaching and effacing E. coli is most commonly seen in pre-weaned dairy calves between 2 and 10 weeks of age but can also be seen in weaned dairy and beef calves. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) however, is seen in calves less than seven days of age and causes an osmotic/secretory diarrhoea and no histological changes.

Differential diagnoses for weaned calves include gastrointestinal parasitism, yersiniosis, BVD, adenovirus, coccidiosis or salmonellosis and may occur concurrently with or predispose to AEEC.

In contrast to ETEC where a K99 antigen ELISA is available, no test currently exists for ante-mortem identification of AEEC and histology is required. Due to superficial location of the bacteria on the luminal mucosa, any autolysis will result in false negatives therefore necropsies need to be performed within 30 minutes of death.

Additionally, these bacteria may only be identified in the large intestine, specifically spiral colon (as in this case) which is not often taken by veterinarians during field post mortems. Specifically, one study identified AEEC in 88.4% of spiral colon samples from scouring calves but only in 11.7% of small intestinal samples. Therefore, sacrificial post mortems of moribund calves with immediate fixation of gastrointestinal samples including spiral colon are required (in addition to other fixed and fresh tissues in case other pathogens or diseases are involved). The lumen of the section of intestine to be biopsied should be flushed with formalin first using a 50mL syringe and 18G needle inserted into the lumen. This will immediately fix the luminal mucosa where the bacteria reside maximising the chance of successful identification histologically.

Thank you to Jason Clark of VetsOne for submission of pristine samples from this interesting case which allowed the diagnosis to be made.

References

· Blanchard PC. Diagnostics of dairy and beef cattle diarrhoea. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 28:443-64, 2012.

· Janke BH, Francis DH, Collins JE, et al. Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli infection as a cause of diarrhoea in young calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 196:897–901, 1990

· Moxley RA, Smith DR. Attaching-effacing Escherichia coli infections in cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 26:29-56, 2010